Featured Artist: Emma FitzGerald

Emma FitzGerald and I met earlier this Spring at Hollyhock Retreat Centre, on the West Coast of Canada. Our first encounter took place while we held our dinner plates and smiled at each other, waiting in line for an Indian inspired menu along with the largest stainless steel bowl of salad greens, picked a brief moment ago from the garden out back. Emma was leading a workshop called ‘Sketch by Sketch: connecting with the world through drawing’. During our stay, she gave a presentation that was open to the community of residents on Cortes Island. There, I learned more about her life trajectory & work as an artist and illustrator- and we began weaving the threads that connect us. On Friday, June 27th, 2025, I had the pleasure to reconnect with Emma from her late nineteenth century house in Lunenburg, Nova Scotia.

Emma was born to Irish parents in Lesotho, a small country in Southern Africa, and grew up in Vancouver, Canada, before moving to Ireland as a teenager. She holds a BFA from the University of British Columbia and a Masters in Architecture from Dalhousie University. In the early stages of her career, Emma worked for Peter Rich Architects in Johannesburg, more specifically taking part in the projects for the Mapangubwe Interpretive Centre and Alexandra Heritage Centre. Her interests are diverse, her approach is always contextual and she is moved by an artistic and down to earth outlook. Unsurprisingly, Emma found herself following her passion for drawing and illustrations. She engages with places and people with curiosity and has an innate ability to translate the feeling of being somewhere onto the page. Her drawings become an invitation to travel, to engage in a sense of wonder, a poetic approach to explore the intricacies of our shared humanity. Emma has illustrated several picture books and starting in 2015 she published the first book of an original series called Hand Drawn showcasing Canadian cities, their landmarks and more nuanced places of everyday life. See the all three publications here: Halifax, Victoria, and Vancouver. I also happen to have observed and later confirmed Emma’s love for hats, eating fresh oysters on the beach, traveling to faraway lands, and spending time in the outdoors. To have a glimpse of her seaside life, sketching workshops, illustrations in the making, and all things that make Emma’s heart skip, follow her on Instagram.

This is the first featured artist interview and as such, I’m grateful for Emma’s trust and patience. Our talk lasted about an hour and produced a 14 page transcript, from which I extracted the highlights below. Throughout you will find audio clips with segments of the interview, so you also get to experience Emma’s stories though her own voice. I hope you enjoy it.

Marina: There you are! How are you?

Emma: Good, I’m a little hot. And you?

M: I’m good, really excited to connect with you. I was just reviewing my notes and I came across the photograph I took of you at Hollyhock.

Emma at Hollyhock Retreat Centre, on Cortes Island, British Columbia, Canada. Illustrations featured are the creations of the folks that attended her workshop ‘Sketch by Sketch: connecting with the world through drawing’ in May 2025.

M: Your illustrations have this vibrant lived-in quality. It’s almost like places themselves are characters. Can you tell me a little bit about the notion of place, your relationship with places, and how that influences the storytelling of your illustrations?

E: When I was a little girl I lived in Canada but I was born in Lesotho, in Africa. And even that is complicated because I was born over the border in South Africa but my birth certificate - I think I told you this when we met, said I was born in Lesotho but that’s where I lived. I think that place for me was like a character. There was a children’s book that was created to raise money for blind people in Lesotho and it told the story of a little boy and the village he lived in, the kind of architecture of the huts and the landscape. I remember my dad sitting down and drawing with me, we were copying the illustrations. That’s a very early formative memory of trying to be a detective and find out as much as I could about where we used to live. When I was 16 years old we moved to Ireland, where my parents are from and I was very lonely so I spent a lot of time in Dublin just walking around drawing. So the city is like… It became my friend, you know? I think this idea of drawing outside and on location forces you to be kind of fast and immediate. So maybe that’s where this almost casualness became important. I think that’s what brings a sense of connection.

M: Yes, there is a sense of fluidity in your lines and drawings. During your talk at Hollyhock, you mentioned that after studying Fine Arts at UBC, you went on to study architecture at Dalhousie. What about the role of architecture and how that background influences your work?

E: Architecture taught me how to work within a certain size of page, how to scale things up and down, and discipline... I think I was always disciplined. Also learning the technology of computer programs. I would learn from my peers because some of them had different expertise. Also being very comfortable with receiving critique because even more than in art school I feel like in architecture school, we were really having to defend our ideas. But also have to learn not to get so defensive that you couldn’t listen to the feedback. When we’re working on a book there’s a lot of this, you need that ability to receive the feedback and take it to a place that no one imagined before.

M: So, I guess what you’re describing is more about the process itself. I guess book making is very collaborative right?

E: Yeah and sometimes it’s a little bit like, not necessarily collaborative. You receive this feedback and then you wonder what am I going to do with that. You have to stay with it and see it through. When I was in my Masters Program at Dalhousie I went to these mountain areas in Lesotho. Let me show you this. This is something we grew up with in the house. I have it now. There is one over there… [Emma showed me several woven textile wall hangings like the one below]

These pieces were woven in Lesotho by women. There is a whole story because I think the Irish came with the government and - this was the same program that my parents did, and they helped the women make it more marketable so that people would buy the pieces.

Years later I met someone in Vancouver and he knew these specific Irish nuns that had the women no longer put grass in the weaving. There is this element of colonizing and dictating the aesthetic but it is depicting this traditional village life, which some of it exists, some of it doesn’t.

E: When I went back during my Masters, I worked in Johannesburg and I did my thesis based in Lesotho. I was really learning the way they make place and the architecture, and the role of women. I think whenever I’m doing a book I try to bring a lot of context into it.

In the book When the Ocean Came to Town I chose to make the main character a black girl, someone who is black but it still looks like Nova Scotia. Because in Nova Scotia there are these very historic black communities that have been here for over 300 years but there is this environmental racism, they have been put to live in the worst places. It’s not overt but I would hope that if a child from one of those communities saw the book, they would see themselves as a protagonist in this positive story. But none of this is written down, this is just me putting a lot into it, I guess.

M: It’s nice to hear about the way your upbringing and personal experience informs your approach to illustrations. Later in my life, my relationship with picture books was largely tied to being a mom and thinking of books for Georgia. And I think for her generation, it was a time when we started seeing people of color being more represented in picture books. With my background I sometimes lean on those books as a way of Georgia being able to understand a bit more of my experience in the world. Because she had a limited exposure to my culture growing up in Vancouver.

E: Yeah that was something that struck me in Brazil. This mixing and it might not be perfect but it’s really real and present. And it’s hard because you also don’t want it to be a token thing. There are many things to consider I guess…

M: Since we just made this reference to Brazil. I was thinking of your book A Pocket of Time about Elizabeth Bishop. When we met on Cortes Island you told me about your travels in Brazil. If I’m not mistaken, you actually stayed in the house that she lived in Petrópolis?

E: Not in Petrópolis, that was in Ouro Preto. In Petrópolis I stayed in this hostel which belonged to Lota’s father [Lota de Macedo Soares, Brazilian landscape designer and architect, who was in a relationship with Elizabeth Bishop from 1951 to 1976]. It’s a very colonial building and now it’s a hostel. It’s close to where they lived in Petrópolis. But later in their relationship Elizabeth bought her own house in Ouro Preto. It’s still there, Casa Mariana. And the man who owns it now, José Niemeyer, he’s an architect. He was roommates with Bishop in the house when he was very young, like in his twenties. I don’t know how it came into his hands. Whether he bought it from her. When the relationship was getting a little rocky with Lota this gave her somewhere else to go, her own little world. She ended up going back to the U.S. and then sometimes visiting it. This back and forth. In that house, I did sleep in her bed. It was very cool but it was also a little ‘Eaw…’ [eerie]. I’m going to Elizabeth Bishop’s house in Nova Scotia this week, on Monday. So you can still go to that house and be there as an artist.

M: Is that the house Elizabeth lived in with her maternal grandparents?

E: Exactly, yes. It’s quite powerful because it’s still being taken care of.

Image from panel discussion about Elizabeth Bishop that took place in Halifax in March 2020. Courtesy of Emma FitzGerald.

M: Did it become a museum of her work?

E: No, it’s just this kind of a retreat center but it’s very low key. I first went there twelve years ago and it was a ‘pay what you can’, you would leave twenty dollars on the table and now it’s two hundred dollars for the week. It’s still very reasonable. Honestly, the people running it are getting older and there’s this feeling of… It needs someone to come in with energy but the location is quite remote. I hope it keeps going. It’s been run as a residency since 2005. It has a historic plaque recognizing its historic significance but it’s still not widely known. Many people would not know about it in Nova Scotia.

M: The book focused more on the time of her life when she lived in Nova Scotia but was there anything that came up during the time you were in Brazil that you feel really influenced, afterwards your experience illustrating the book?

E: Oddly, there is that image of the porch with the grandmother and the hair flowing with the wind. That was quite special and significant because I actually did that very early on. I did all the rough sketches and they were approved, then I went quite far with that one and it brought this element of magic. I hadn't thought of it but there were definitely times in Brazil when the mist came in, or you’re down by the ocean and the women are doing their Orixás. Her house in Ouro Preto has a narrow balcony overlooking the town. Somehow this porch also has this significance of looking out over the landscape. So, I think there are echoes there…

M: I actually wasn’t super familiar with her work and leading up to our conversations I’ve been reading her poetry and I’m in awe and as I learn more about her, there was someone who said that in her entire life she published 101 poems. She was very meticulous and a perfectionist in the way she revised them.

E: What was special when I spent that first time at the house, 12 years ago by myself, I was reading this book that has all the letters between her and her editor at the New Yorker. And they would write a letter all the way from New York to Brazil about moving one comma, and she would have to write all the way back. Maybe there’s something about a slower time and being in Brazil, very far away. She had this whole life in New York, her editors and stimulation but she was kind of… I guess that’s what I find travel does to me. It slows down time. It allows you to gain some perspective. I guess that’s what she found in Brazil and it’s what travel does for me. Yeah, you just get this juicier version of time.

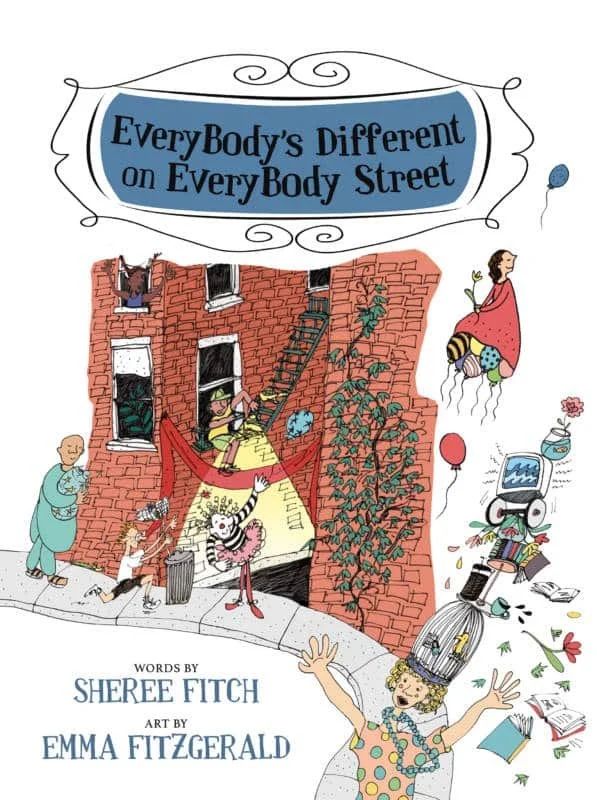

M: That’s a beautiful parallel. And you were there breathing the same air. If it’s okay I’d like to ask about Everybody’s Different on Everybody Street - which by the way, it was such a treat to have you read the book to us at Hollyhock. I loved how you included us in the reading. As adults, whenever we have an opportunity to do something that feels spontaneous, more childlike, it’s so nice. With this book in particular, I was thinking about picture books as a way of helping kids make sense of the world. This book came out in 2018 before the pandemic and you told me the background story… The pandemic was a time of crisis for mental health and addiction- things were made so much worse by that social isolation. What are your thoughts about this idea of picture books as a vehicle of bringing up subjects that are hard to talk about?

Yeah, this story was written quite a long time ago, maybe 2001 and back then it was so much more taboo to talk about mental health. I think on one hand there is this positive that by the time we did the actual trade book, it had become a little bit easier to talk about. At the same time, issues that compound with mental health, housing crisis, inequity, are just getting more and more difficult. It’s interesting when I go to schools in Halifax and I read the part about ‘some of us live in the park’. When I moved to Halifax there weren’t tent cities. I knew them from Vancouver and now it’s a common thing even with our cold winters. Honestly, sometimes I question, am I skilled enough to bring this up? Do I have a context and usually I ask: Who do you think in this page is living in the dark? The person who looks sad? The person in the window in the dark...? The blind person? Or the person in the park because they are feeling left out?

E: I think there is also something nice about a little bit of ambiguity and space so that they can reflect and think about it and maybe ask questions later. Or even know that it’s safe to bring it up as a topic. Including the person on the roof who looks quite sad, again it was a little hard to know how bad to make it. At first there was actually a big brick wall on that page, and it had darker colors. It was actually Sheree [Sheree Fitch, the author] who saw it and thankfully that was one of my first tests doing all the colors. I was a little bit excited about this trend of making sad books. I thought: I’ll make it shadowy. And she was like, ‘No, it actually still has to look inviting and colorful. Make it approachable and the words along with what’s in the picture will give it the depth.’ I ended up liking that approach of how it invites you in and then it can be something more serious. I feel like my city books are a little bit like that too. At first, it looks light but there can be a little twist, whether it is the words or someone looking a little lonely. You feel a pathos. I think it’s this balancing act of making sure people will come to the table to hear what it’s saying.

M: I see what you’re saying Emma. Because if the person, if that’s where your mind wants to go, it takes so little, right? I was wondering whether you want to share a favorite picture book that was a part of your childhood, either you loved the book itself, or because of who read it to you…

E: There’s a few. I think it was the first book that I felt like I read myself. Maybe I had just memorized it because my parents were reading it to me so often. It’s a little like Everybody is Different on Everybody’s Street it’s so easy to remember because it rhymes. I think it was Each Peach, Pear, Plum by Jannet and Allan Ahlberg. It’s a husband and wife and I don’t know which of them did the illustrations but it’s kind of like ‘Woodland’ with lots of animals. It’s super super charming, all these little details, fruits, characters, and animals. I had this pride because I felt like I read it myself.

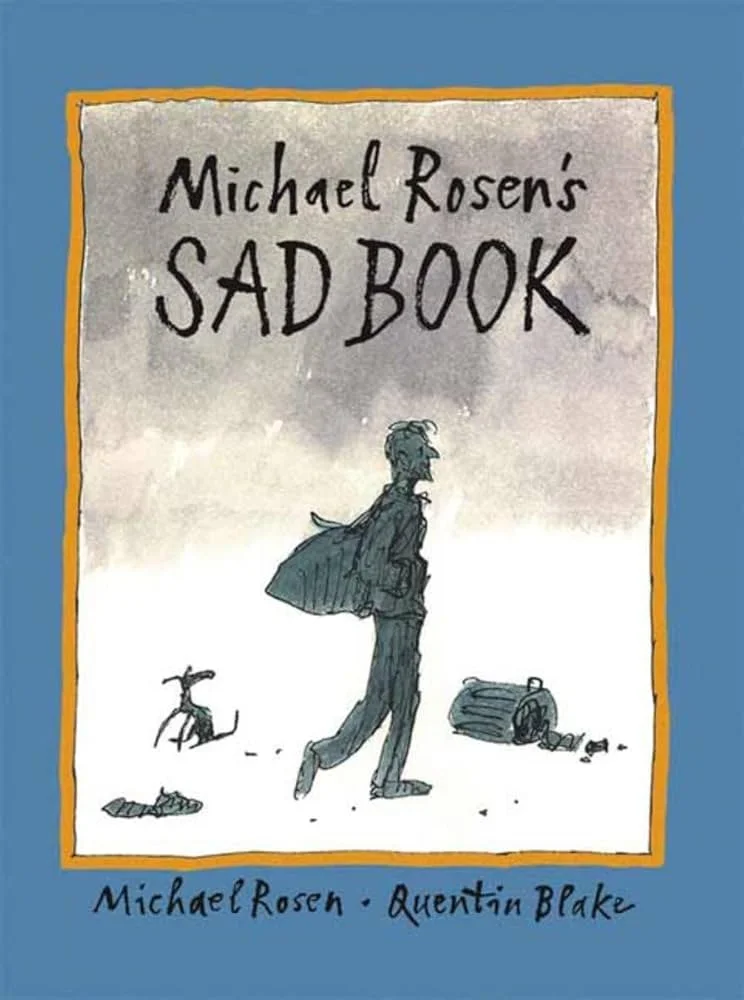

Funnily enough, James and the Giant Peach - the fruit themes. This was my first novel that I read. Again, I don’t know how much my parents were reading with me but it has these beautiful detailed illustrations. People looked at my work and they thought about Quentin Blake who illustrated many of Roald Dahl’s books. I never looked at the drawings and thought ‘Oh, I need to draw like him’ but they must have soaked in and gave me permission to be loose like this.. Thinking, ‘Oh yeah, that’s a valid expression’ and the fingers that are like “Whaaaa…”

I didn’t learn about this until I was an adult and was just starting to illustrate books. It was actually also Quentin Blake illustrations but the book is by a British poet called Michael Rosen. And it’s about his grief after his son died, when he was quite young. So interestingly, because Sheree ended up losing her son just before the book was published, Sad Book helped me understand that there can be lightness and the dark together. It’s giving people permission to feel sad and what a shared experience it is.

M: It’s nice to know that context, because sometimes we’re going through difficult times, through grief. it’s so hard to see that light. So I think it’s wonderful you’re giving me that context and how it’s behind the stories of these books. How something uplifting can emerge from a time of such great sadness. Is there anything else you’d like to share, any books or projects coming up?

E: I’ve been working on a children’s cookbook for the lunch program in the schools here. It’s a proud moment for Nova Scotia. It’s not perfect yet, but there are lunches in all the schools and it’s a priority to make sure people have food. We have a lot of poverty and food insecurity and also this branching out to salad bars and food forests, seeing a bigger context for learning and being involved with food. I also go into schools a lot to draw and talk through our Writers’ Federation. One time, I was telling the kids ‘I’m working on a cookbook about your lunch program’ and they were like “We like the Mi’kmaq stew!” which is a traditional food from the Indigenous peoples here. That wasn’t around when I was a kid. The notion of eating the Indigenous foods from the place you live. I think that would inform more layers of understanding. It’s interesting to me.

M: Are the recipes meant to be things the kids can be involved in making as a part of the kitchen programs?

E: A little bit. Some of the schools do have a cooking program for the kids and some of the kids are provided with lunches but the book will share with them how the foods were made and if they want to make it at home, they can. The illustrations are also sharing the context of different kinds of learning that is happening at school around food.

This project is not with a publisher, instead it’s with an NGO called Nourish Nova Scotia. I guess there was a little bit of trust on my behalf. The woman who contacted me is part of this not-for-profit but she has written a cookbook herself. She used to have a café but suddenly, through this project, she got to be an editor. I had to set my boundaries around the amount of work that I would be able to put into it. When you work with a publisher, to be very honest, it’s kind of crazy, you have no boundaries because you’re so excited about the project. You’re never being paid by the hour, right? It’s this labor of love. But the work itself ends up opening these other doors. With this project I had to be a little more pragmatic. I think we still managed to do something I’m excited and proud without also giving them unlimited access to me. That was a learning experience. It feels good that I trusted my instincts.

M: You just mentioned how because of the Writers Association you end up spending a bit of time at the schools. Has there been room to integrate what you found out, sort of what is it that the kids enjoy….

E: We visited one of the schools with Nourish Nova Scotia and got the kids to draw what their favorite foods are and they were pizza, sushi, ice cream [laughs]. But in the context of us working on the cookbook, the drawings are in the hands of the designer now. It’s a bit tricky, I wonder whether the kids will remember and feel like ‘Oh you didn’t put mine in.’ My hope is that it gets put on a website at least so that there is a gallery with all the drawings. I think the kids were quite proud. I also got them to draw the cover of ‘what if you had a cookbook’. Very cute.

M: Based on your experience as an artist, writer, and illustrator, what is a piece of advice that you would share with emerging illustrators?

E: I guess trusting. But continuing to just be disciplined. I used to draw a lot when I traveled, then I submitted those drawings to a publisher as a portfolio. They were polite about it but nothing came of it, but then… It was only when I lost my job as an architect and I had to draw for my income. I started drawing a house a day in my neighborhood, and it became this book [Emma picked up a copy of Hand Drawn Halifax to show me].

Photo courtesy of Meghan Bangay Collins.

For me, it’s that discipline of doing something everyday, even if it’s for an hour, and after a month you stand back and you’re like ‘Oh, I have these thirty things and I can pick ten of them’. And then that’s what I took to a publisher as my concept. I guess when something adverse happens, say lose your job, this can be an opportunity. Seeing those moments when you have that time to be creative and really soaking that up and just trusting because we can’t necessarily control the outcome.

M: That speaks beautifully to where I’m at personally in life. I really appreciate that. Thank you so much Emma.